Today and tomorrow’s EV batteries and fuel cells

Electric vehicle batteries and fuel cells can be viewed as competing technologies, but in reality both have a part to play in decarbonising transport. Emma Richardson from the National Physical Laboratory, looks at the challenges that both technologies face before full commercialisation can happen

The number of alternative fuel vehicles on the road is rapidly increasing. The Guardian recently reported a record 4.4 per cent of new cars sold in May 2017 were hybrid or pure electric models.

These vehicles – currently dominated by electric (powered by batteries) and fuel cell (powered by hydrogen) technologies – are becoming more popular as people become more aware of the impacts of urban air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

According to the Royal College of Physicians, there are around 40,000 premature deaths annually attributed to illnesses relating to air quality. On top of health impacts, the transport sector also accounts for over 20 per cent of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions.

These are critical issues that require addressing, and have influenced the UK government’s recent announcement that the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles will be banned by 2040. As a result, car manufacturers have begun to shift their R&D focus towards low carbon technologies – the two leading technologies being batteries and fuel cells.

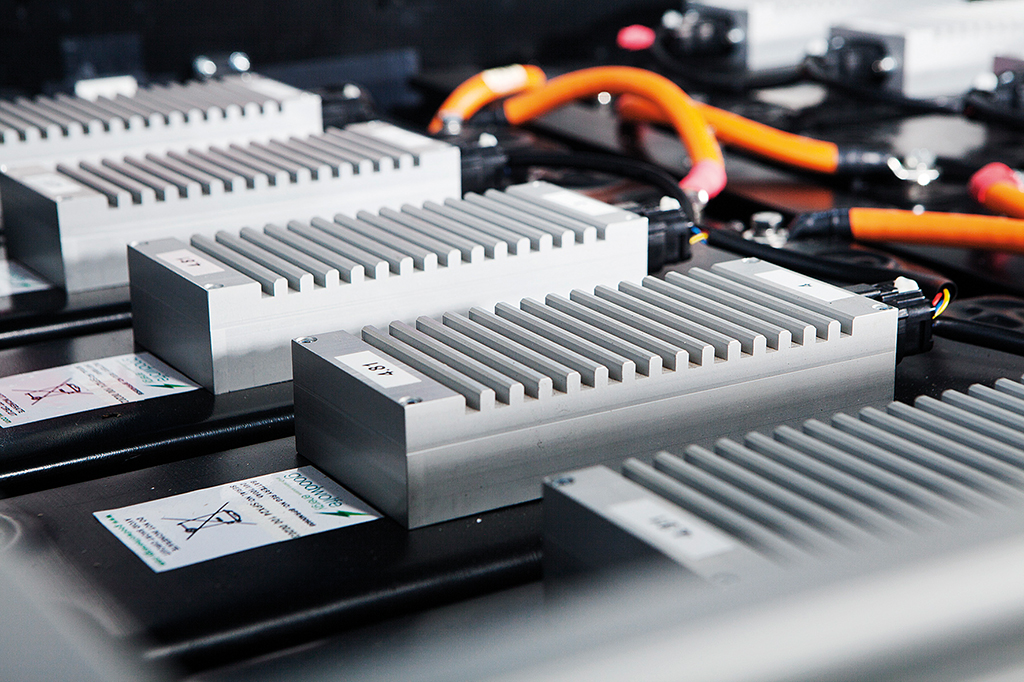

Electric vehicles

EV penetration is currently less than two per cent in the UK, but the Committee on Climate Change predict that EVs could make up to 60 per cent of new car sales by 2030 (in their high uptake scenario). Along with the government’s aspirations for a ban on carbon‑intensive vehicles and the launch of the Faraday Challenge, there are currently significant efforts being made to ensure the UK leads the world in the design, development and manufacture of batteries for the electrification of vehicles.

As the energy density of battery cells increases to meet the demanding requirements of emerging markets, including transport and also grid storage, the effectiveness of battery safety features becomes ever more critical. Thermal runaway of high energy density batteries is of increasing concern to manufacturers and end users, highlighted by the recent Samsung mobile phone fires and the grounding of the Boeing Dreamliner fleet a few years ago. Just one major incident of thermal runaway occurring in an EV could severely set back the industry.

NPL’s research into battery technologies is primarily focused on the development of in situ diagnostic techniques, modelling tools and standard test methods to better understand battery performance and degradation. This is helping industry to develop cheaper, longer lasting and safer batteries.

Our recent research into failure mechanisms in Lithium-ion (Li-on) batteries – the kind you would find in smart phones, laptops and electric vehicles – has allowed, for the first time, 3D imaging of thermal runaway occurring in real time within the cell.

This technique provides a better understanding of what happens chemically and physically when a battery cell fails, allowing for improvements to the design and safety features of Li-on batteries to be made. This research was carried out in collaboration with UCL, NASA, the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the European Synchrotron Research Facility (ESRF) and recently won The Engineer’s 2017 Collaborate to Innovate Award in the Safety and Security category.

A second life

Recycling and re-use of batteries is also a major issue that is often overlooked. Batteries require the use of finite metals which need mining, therefore it is important that resources are used as efficiently as possible. NPL is developing standard test methods for automotive batteries at end-of‑life to make it easier to use them in second life applications, such as for grid storage. This will not only reduce the upfront cost of EVs, but ensure that the battery is being used to its full capacity.

It will take a concerted effort from industry, academia, government and research bodies to address the current challenges facing EVs, including high cost, limited range and a long recharging time. NPL have recently led a workshop with the UK battery community to attempt to bring together expertise in tackling these priority issues. The workshop aimed to identify and prioritise measurement issues facing UK manufacturing capability in next generation high energy density batteries and the outputs will be published in our upcoming report ‘Energy Transition: Measurement needs in the battery industry by the end of the year.

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles

Another promising solution for decarbonising transport is the use of hydrogen as a fuel. Hydrogen can be produced at any location where there is an electricity source for electrolysis (using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen) and a suitable mechanism for storage.

Most of the hydrogen refuelling stations in the UK currently produce hydrogen fuel in-situ via electrolysis and are powered by grid electricity. The gas is then stored in high-pressure tanks on-site and dispensed to the vehicle in a similar method and in a similar refuelling time to conventional petrol and diesel cars. Whilst driving, hydrogen passes through the fuel cell stack and reacts with oxygen to produce electricity which powers the vehicle.

According to the International Energy Agency, deploying a 25 per cent share of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) on to the roads by 2050 ‘could contribute up to 10 per cent of all cumulative transport-related carbon emission reductions’ globally.

The UK H2Mobility report from 2013 predicts that in the UK, we could expect 1.6 million fuel cell vehicles on the road and 1,100 hydrogen refuelling stations in operation by 2030. This would provide substantial benefits to air quality and decarbonisation efforts, as the only emission from the tailpipe of FCEVs is water. Currently, FCEVs are better suited to longer‑distance road transport such as fleets of vans, small boats, buses and HGVs than EVs, as they have a much faster refuelling time and longer range.

However, like EVs, this emergent technology and its required infrastructure create their own unique challenges.

Purity analysis of the hydrogen fuel being delivered to FCEVs at the refuelling station is essential, as even trace amounts of impurities (down to the parts-per-billion level) can quickly degrade the fuel cell. This is a serious concern for the fuel cell manufacturers and automotive industry, as impure hydrogen would impact the reliability, lifespan and ultimately the mainstream commercialisation of these fuel cell technologies.

To avoid this, an international standard (ISO 14687-2) was established which requires measurements of 13 impurities to be taken before the fuel can be used in a FCEV. Due to the complexity of the measurements required, NPL is currently the only known laboratory worldwide accredited to provide calibration gas standards and validated methods to comply with the purity specifications. These stringent requirements could therefore eventually become a bottleneck for the commercialisation of fuel cell vehicles.

Fuel cells and electrolysers

NPL has also developed a range of novel in-situ measurement techniques, modelling tools and standard test methods to support commercialisation of fuel cells and electrolysers. For example, NPL has overcome the challenges of in-situ measurement – specifically in polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) fuel cells – by developing straightforward methods and monitoring systems to be implemented in real systems.

Also, by continuing our active participation in the development of new and improved international standards, primarily via technical committees in ISO/TC 197 (Hydrogen technologies) and IEC TC 105 (Fuel cell technologies), NPL will also be key in transferring best practice to industry.

Today, there are only a handful of hydrogen refuelling stations nationally, but through funded projects such as Hydrogen Mobility Europe (H2ME), there are plans for 65 stations across the UK by 2020 and the numbers continue to grow. Measuring the impact that the increasing number of electrolysers may have on the UK electricity grid, especially in terms of the high electricity demand required, will be another challenge that will require addressing to ensure that the grid is fit for purpose and able to cope with the potential demands of large scale electrolysis.

The UK has internationally prominent measurement capability, as well as established R&D institutions, and tackling the challenges currently facing hydrogen as a decarbonisation solution could enable us to host a world‑leading hydrogen industry. These challenges were identified and prioritised by NPL and stakeholders from across the sector in our recent report ‘Energy transition: Measurement needs within the hydrogen industry’.

Next steps for low carbon tech

It is evident that batteries and fuel cells are among the leading candidates to facilitate the transition to a low carbon future. For many they are viewed as competing technologies, but the reality is that given the scale of the challenge that decarbonising transport represents, both will have a part to play.

There are cross-cutting challenge areas that face both of these technologies which require continued research if they are to achieve widespread commercial uptake. These include the need to reduce cost and improve lifetime, as well as increase the roll out of necessary charging and refuelling infrastructure. As is often the case with emerging technologies, a ‘chicken-and-egg’ problem can occur where lack of refuelling and charging infrastructure can reduce vehicle demand, which in turn makes the infrastructure not commercially viable.

Although it is essential to deal with this problem, it is also important that the safety and performance of these technologies are not overlooked by the industry in the current rush to be at the forefront of decarbonised vehicle development.

NPL will continue to work closely with stakeholders across the battery and hydrogen industries to address the range of challenges still hindering their wide commercial uptake, as robust measurement often underpins the solutions to these challenges. With continued research, the reality of a low carbon transport system could be just around the corner.